If you can, please donate to the legal fund via GoFundMe or PayPal. Aaron Greenspan is suing me, Elon Musk, and Tesla and I really need your help.

Previous Chapter: Me and My Model 3 | Next Chapter: Trolling the Trolls

For people coming from Twitter: This chapter is part of the story of how Aaron Greenspan’s charity PlainSite has stalked and harassed me for two years. If you’re new to the story, start at the introduction or check out the table of contents. New chapters will be posted as they’re ready. Subscribe to email updates to have them sent straight to your inbox.

The conservation was surprisingly fun and engaging. The anti-Tesla accounts joked with each other and made memes that were hard not to laugh at, even if you didn’t share their viewpoint. It was easy to get hooked following the story on social media. Using my @OmarQazi Twitter account, I debated Tesla with some of these anonymous accounts so often that I started to see some of them as friends. Daily discussions and debates about Tesla with accounts like @ETeletubby and Pivotal Capital were spirited, but also still fundamentally cordial, respectful, and educational. It seemed like Twitter at its best: Connecting you to different people with diverse views in a beautiful way, and putting the pulse of the world at your fingertips.

At first I thought the anonymous troll accounts were just random people who didn’t want to use their real name on Twitter, but after following a few of them I quickly realized that there was something unusual going on. These weren’t just ordinary people operating independently and tweeting for fun. They identified as part of a closely-knit group that had come to Twitter to make some money.

The trolls called themselves $TSLAQ: a reference to the Q that gets added to a stock ticker symbol when a company goes bankrupt. They all repeated the same message, insisting with stubborn confidence that Tesla was about to go bankrupt at any minute and that the business was nothing more than a complete fraud. This viewpoint surprised me, as it didn’t match with what I was experiencing driving my Model 3 at all. Did people really believe all this misleading nonsense?

Indeed, people did. What I saw unfold before my eyes over the rest of the year was one of the most astonishing, most impressive social media influence campaigns in the history of the internet. Let me tell you, this disinformation campaign made the election manipulation tactics Russia’s Internet Research Agency used against the United States look like a game of Patty Cake.

For a long time, TSLAQ somehow managed to completely dominate and control the narrative around Tesla in the public conversation. It was shocking how effective they were –– everyone from TSLAQ, to Tesla fans, to Elon Musk can agree on that. You’d hear these anonymous accounts spout complete nonsense on Twitter and laugh at them, but then the next thing you knew there’d be a story in the news featuring the exact same absurd talking points nearly word for word. Their influence (especially with popular financial news organizations) was shocking to anyone who used Tesla products and knew that most of what they were saying was either flat out untrue or grossly exaggerated, with only the smallest kernel of truth at the core to sustain the illusion of credibility.

I tried to share my experiences with the Model 3, correct any inaccurate statements they made, and reason with them, but I quickly realized they didn’t want to be convinced. They wanted to do the convincing.

Anyone who replied to TSLAQ tweets without sticking to the party line was instantly mocked and ridiculed by a swarm of nasty anonymous trolls, no matter how misleading or outright false TSLAQ’s claims of the day happened to be. If you started to ask too many questions or showed even the slightest hint of independent thinking, you’d be immediately blocked across the entire TSLAQ network via the TSLAQ blocklist.

The TSLAQ blocklist is maintained by Paul D. When TSLAQ members get even the faintest whiff of an account that doesn’t agree with their messaging, they simply tag Paul who quickly adds the account to the list, which features thousands of Twitter accounts deemed uncooperative. Since the vast majority of TSLAQ accounts and even some mainstream journalists subscribe to the blocklist, once an account was spotted it would be blocked by the entire TSLAQ disinformation network. The blocklist was one of the main ways TSLAQ abused Twitter’s safety features to manipulate the conversations people saw on Twitter for their own financial benefit. The leaders of the campaign could control exactly what their followers (and even some journalists!) saw on Twitter, distorting their perspective significantly.

Why were all these accounts spending so much time posting negative information about Tesla? Who would care so much, and why? The answer quickly became clear as more and more of these anonymous accounts linked me to tweets from the group leader, a man who seemed to be at the center of driving the TSLAQ movement forward on Twitter. The account was anonymous and used the screen name @TeslaCharts.

I went to follow him, and noticed a line in his bio that explained what was going on: “Disclosure: Short Tesla via put options“. That meant that TeslaCharts, like most other TSLAQ accounts, had bet money that Tesla’s share price would fall, predicting that it would soon reach $0.

If TSLAQ could get the stock price to fall they would make a lot of money fast, but if the share price went any higher they’d be completely screwed by billions of dollars in collective losses. Because of these stock market bets, I’m sure you can understand why they desperately needed to do everything they could to try and convince investors to sell Tesla shares and tank Tesla’s stock price –– even if it meant routinely straying from the truth.

TeslaCharts called it an “experiment in social media” –– an experiment in weaponizing social media for market manipulation and securities fraud. It was amazing how such simple techniques could have such a dramatic persuasive effect. This wasn’t rocket science, after all: The medium of Twitter was new, but the classic short and distort scheme is one of the oldest securities fraud tricks in the book. For those who aren’t familiar with TSLAQ, let me give you a few examples of how they manipulated and distorted the conversation around Tesla.

The Block List

The blocklist turned out to be a powerful persuasive tool. By blocking out any dissent, TSLAQ could create Twitter threads that looked like everyone was in universal agreement, with no one to point out the glaringly obvious flaws or inaccuracies in their logic. With any new technology like electric vehicles, it’s very easy to come up with some misinformation that most of the general public won’t question (“Who wants to wait to charge it every day?”) even if every EV driver knows it’s not true (“Who wants to stop for gas when you can charge while you sleep or Supercharge?”).

Psychologically, humans are hardwired to agree when they think everyone else is in agreement. It’s a completely subconscious survival instinct, so most people don’t even realize it’s happening. When you join a conversation and there’s consensus, you don’t want to shit in the punchbowl. You want to be nice, fun, and agreeable. Twitter users who stumbled on TSLAQ threads had no idea that all opposing viewpoints had been blocked from the conversation, but they were still influenced by a one-sided discussion taking place in an alternate reality of collective delusion. Some of these Twitter users included influential journalists and regulators, who TSLAQ would seek out and tag in their posts to attempt to influence their thinking. Friends of the movement would be promoted. Enemies would be smeared, mocked, harassed, and threatened.

When a TSLAQ member subscribed to the block list, their account would be hidden from anyone with independent views on Tesla. But more importantly, TSLAQ would still be able to see all of the tweets from people on the blocklist with just the push of a button. Some Tesla customers and fans may have wanted to block anti-Tesla hate groups from seeing their tweets to protect themselves from online harassment, but it’s difficult to do so when you’ve never seen the account stalking you before because you’re already blocked.

The result is that TSLAQ was able to operate in the shadows, completely invisible to most people who might have called them out, while they stalked, threatened, and harassed Tesla customers freely. I call this social media manipulation strategy “block & stalk“. Normally you block someone because you don’t want to interact with them, but in this case, the blocking was designed to make stalking easier and more fruitful. It also protected TSLAQ from enforcement action by Twitter, because Twitter’s rule system is based on user reports. If you can’t see an account, you’re not going to report it no matter how often it violates the rules. TSLAQ friends benefitting from the rules violation won’t report it either.

Distortion through Engagement

TSLAQ would like and retweet negative tweets about Tesla while suppressing or casting doubt on positive ones. Coordinated manipulation of social media is really as simple as that. Anytime someone posted something negative about Tesla or electric vehicles in general, TSLAQ would make sure everyone in the world saw it. When there was good news it was always a lie, a fraud, or a fake. No matter how positive the news, they would share whatever rhetoric they could come up to gaslight the public into doubting whether the electric vehicle revolution was really happening at all.

Simply liking and retweeting is pretty innocuous behavior, but can really distort the world people see in their social media feeds when you have thousands of accounts coordinating to push a pre-designed message. When you launch any new product there are always problems at first, and the Model 3 was no exception. Suppose hypothetically that at some point in the Model 3 ramp 1 out of 1,000 cars had a problem, meaning that 99.9% of the cars sold were perfect. (This is just an example, not real data.) Well, if Tesla is making 1,000 cars a day that would mean 1 car with a problem is produced every day. TSLAQ would find that car and make sure it’s the only car people saw and talked about that day simply by liking, retweeting, and replying to the photo in question.

Now all of a sudden casual spectators see a new picture of a Tesla with a different problem every day. You’re not going to investigate it and ask about the stock market bets of the people posting. You’re just going to scroll and think “Man, these Tesla Model 3 cars seem like they suck”. Even if the reality is that 0.1% of cars have a problem, a dishonest group of people can make the situation appear very different on Twitter. And of course, nobody is posting a picture of every Toyota Camry with an issue. The leaders of the campaign know it’s mostly bullshit, but some of the less intelligent lower-ranking members of TSLAQ might start to actually believe what they’re saying. Any time you scare someone away from buying a Tesla you hurt the business and help your short position, so TSLAQ would do this kind of thing a lot.

With a huge market for any negative Tesla content, there was a strong incentive to fake complaints and pose as Tesla customers. A common trick would be to buy an old Twitter account that had been unused for years from hackers and then use it to post complaints about Tesla that featured someone else’s photos. These complaints looked completely genuine to everyone except the person whose car photos had been stolen. To the public these daily viral tweets looked completely real, while only a few Tesla owners noticed that the accounts behind them seemed to be missing basic information that any real Tesla owner would have known. (For example: “Is that a Long Range or Standard Range car?”)

Paid in Attention and Stock Options

Social media gave TSLAQ a way to recruit soldiers to their smear campaign without having to pay anything at all. It turns out you can pay people to help with just likes, followers, and friends. Many people will be more than willing to work just for attention.

For example, in February 2018 Aaron Greenspan’s charity’s Twitter account @PlainSite had just 400 followers. After joining TSLAQ, it grew to nearly 5000 followers by September 26, 2019 –– a 10x jump from joining TSLAQ.

Beyond that, TSLAQ leaders would instruct their followers on how best to short Tesla stock and advise on optimal strategies for trading TSLA options. The belief among TSLAQ disciples was that shorting Tesla would make them fabulously wealthy, so they worked extra hard believing they would be paid well for good work. Meanwhile, the leaders of the campaign didn’t have to put up a single dollar of cash themselves to fund this troll army. It may have been one of the first-ever crowdsourced short and distort campaigns. It was a giant stock manipulation and securities fraud scheme, all coordinated and executed completely out in the open for anyone to see.

Community

There are a lot of lonely people online. Fostering a sense of community among members of TSLAQ was key to the recruiting effort. Although the real intent was to use people as pawns to try and push down Tesla stock (often ruining their lives and finances in the process), the public message was: “We are all best friends working together to fight this enormous fraud. This is so fun!”. Just make sure to stick to the script, or all your friends will turn on you in the nastiest way. A few short sellers account like @MartianShort were brave enough to call out the nonsense, even though they continued to short Tesla and believe the stock was overvalued. They were excommunicated from the entire community, placed on the blocklist with the bulls, and smeared by TSLAQ leaders in retaliation for speaking up.

However, the closely-knit TSLAQ community lead to more anonymous troll accounts being created every day and even brought in some people who were willing to speak using their real name. Of course, the only thing better than spreading anti-EV propaganda from an anonymous troll account is convincing someone to repeat that propaganda under their own name, leveraging their reputation. If you can get someone to repeat what you told them, nobody will know that an anonymous short seller betting against Tesla stock came up with it. That made the campaign look far more natural and authentic. Unfortunately, many of these recruits roped into the TSLAQ community ended up losing their life savings –– but amazingly, they said they still say they had fun doing it.

“As crazy as it sounds from someone who lost the vast majority of his net worth, I view [TSLAQ] as a positive experience. I learned a ton, made some mistakes that I won’t make again, and had some laughs in the process”

They didn’t just recruit random Twitter users either. They wanted people with influence. If TSLAQ could help promote someone’s book, or publicly compliment them on an article, then boom: Now you’ve got an author and a journalist on your side. Who doesn’t like feeling appreciated, even if you’re just being used? TSLAQ evolved to become a coalition of anyone and everyone who didn’t like or felt threatened by Tesla –– including employees of legacy automakers.

Quantity over Quality

During the heyday of TSLAQ, most troll accounts posted an insane amount of tweets. If you look at the TeslaCharts screenshot above, he has 84,000 tweets since the account was opened on February 12, 2018. If you assume 8 hours of sleep and 16 waking hours a day, that means the TeslaCharts account has posted a tweet every 11 waking minutes since his disinformation campaign started. When does he make the charts? This is just one of the thousands of TSLAQ accounts. How do you keep the voices of real people from getting drowned out in a sea of insanity and illogical fervor? Who is going to tweet real information about their Tesla that often? They were always awake, and always on top of spinning the latest news. The truth was completely buried under a mountain of lies.

Pseudo-Research

Tesla short-sellers would send planes over certain key areas of Tesla’s supply chain to take pictures, and also send people out to surveil the properties on the ground as well. This is pretty common for people who are doing short research. These operatives called themselves “Shorty Air Force” (SAF) and “Shorty Ground Force) (SGF), respectively.

This kind of pseudo-research could be quite persuasive because it seems like direct primary evidence of what was going on at Tesla logistically. The only problem was that the data was often interpreted poorly, with a tendency to jump to incorrect conclusions that reflected a poor understanding of Tesla’s business.

Users following the posts also started to get conspiratorial, with many speculating that Tesla wasn’t selling cars at all and instead just moving them from place to place to hide them from the short-sellers. That turned out to be false. However, when someone says “Here’s a photo of the Tesla factory and here’s what it means”, the simple fact that there is a real photo seems to give the analysis some credibility. Every lie was built on a kernel of truth, blurring the line between fact and fiction.

Despite the hard work of many TSLAQ members taking daily pictures of parking lots around the world, the data did not help prevent tens of billions of dollars in short losses. Due to the prevalence of misleading framing, dishonest interpretations, and conspiracy theories Tesla bears ignored the growth that should have been apparent from their own surveillance records.

“I know you are, but what am I?”

Another key strategy TSLAQ employed to deflect criticism was psychological projection, also known as the “I know you are, but what am I?” strategy. The strategy is very simple: When you know you’re doing something wrong, falsely accuse your opponents and critics of the exact same conduct that you are knowingly and willfully engaged in. Loudly and frequently proclaim how evil such conduct is, and how it shows what a terrible person the falsely accused is. Now, nobody will suspect that you’re doing the same thing.

It sounds stupid, but it really works. Imagine you saw someone on TV every day campaigning against the ecological harms of taking long showers. You wouldn’t expect that person to take a 2-hour long shower every morning, would you? Even if someone does point out the hypocrisy, it then becomes a he-said-she-said situation and the audience is left with the work of analyzing and judging the claims for themselves. Few care enough to take the time to do so. Most just shrug and walk away.

For example, a common criticism of TSLAQ was that their negative posts were motivated by their own financial incentives rather than a desire to assess Tesla’s business impartially. To deflect this legitimate concern, TSLAQ frequently accused Tesla customers of being secretly paid by Tesla to promote the company. Of course, the reality is that Tesla’s customers are paying Tesla –– not the other way around. Some people speak up because they love the products, and others speak up when they don’t. Nevertheless, in the post-truth era anything repeated often enough starts to sound true. Similarly, frequent false accusations of “fraud” and “imminent bankruptcy” against Tesla masked the fact that the TSLAQ campaign itself was a clear short and distort securities fraud scheme, and that short-sellers were rapidly bankrupting themselves with their bearish Tesla positions.

War Breaks Out

As time went on and TSLAQ grew larger and more powerful, the focus shifted from spreading rumors of Tesla’s supposed impending bankruptcy to actually trying to bankrupt the company themselves. If Tesla wasn’t going to go bankrupt on its own, TSLAQ would do everything they could to push the business over the edge with a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Self-fulfilling Prophecy

TSLAQ’s “self-fulfilling prophecy” strategy worked something like this:

- Tell customers not to buy a Tesla because bankruptcy is coming.

- Tell the suppliers to get their cash up front, because bankruptcy is coming.

- Tell investors to run because, of course, bankruptcy is coming.

It doesn’t matter if the rumors you spread are true or not. If there wasn’t a danger of bankruptcy before, there sure is one now. If there really was a danger of bankruptcy before, now you’ve made certain that it will happen much sooner than it would have otherwise.

It doesn’t take that many people coordinating together to really harm a business, and that’s exactly what TSLAQ did to Tesla as they struggled through the ramp of the Model 3.

This growing phenomenon was recently described by another company that was the victim of a short and distort attack for an article in Institutional Investor Magazine:

“The reality is if enough of them pile on and write enough bad stuff, they can destroy companies. I watched it from the inside. They called our customers and they were making shit up,” bemoans Fichthorn, pointing specifically to a short-seller rumor that the FBI was at the company’s headquarters. It wasn’t.

The Dark Money Secretly Bankrolling Activist Short-Sellers — and the Insiders Trying to Expose It, Institutional Investor Magazine

Psychological Warfare

The goal of the psychological warfare campaign was to harass Elon and other Tesla executives relentlessly on Twitter to make them sad, angry, and demoralized. Take down the company’s leaders and stop them from tweeting, and you’ve made enormous progress towards bankrupting the company. Since Tesla doesn’t advertise at all, social media (especially Twitter) played a key role in getting the word out about Tesla. Shutting down Elon Musk’s Twitter account would be like shutting down all advertising at General Motors: Completely catastrophic for the business, and the stock by extension. So naturally, that’s what TSLAQ sought to do.

Anonymous TSLAQ trolls published an endless number of hurtful and harassing tweets in Elon Musk’s replies and tagged him in tweets that taunted him and attempted to provoke a reaction. They realized they could make Elon appear unhinged by aggressively showcasing his reactions out of context while hiding what they had done to provoke his reaction.

In just one example, they sent daily messages to known members of the Autopilot team for years telling them they were murders and would have blood on their hands. They warned them they’d face criminal charges, a completely bogus threat meant to unnerve employees and disrupt Tesla’s business. In reality, Autopilot is a breakthrough technology that represents the biggest safety enhancement in motor vehicles since the introduction of the seatbelt. Anyone employed by or doing business with Tesla was a target of TSLAQ’s psychological warfare campaign. Later the campaign was extended to target Tesla customers and fans as well.

June 2018: Martin Tripp

With Model 3 production running behind schedule in 2018, TSLAQ began recruiting Tesla employees to join their short and distort campaign against Tesla. How do you convince Tesla employees to turn against their own employer? Simple: Just find someone unhappy and disgruntled, and promise them you’ll make them rich. After all, if an employee could surface internal information that would bring down Tesla stock nothing would prevent them from placing their own short-selling bets to profit from the decline, or receiving a cut of gains from a balance sheet partner. Worried about legal trouble from Tesla? Don’t worry about a thing –– TSLAQ promised to cover that too. That is, in a nutshell, how TSLAQ recruited Nevada Gigafactory employee Martin Tripp.

Tesla had an internal database called the “Manufacturing Operating System” that they used to track every production problem across their factory. Every time there was a problem in any part of the production line, the procedure was to take a picture showing the problem with the part, and log it in the database. Tripp had enough access to query the database for every single photo showing a production error, and export all kinds of confidential production info outside the company. He sent it to journalist Linette Lopez, who published some of the leaked data in a series of scathing articles for Business Insider.

When Tesla found out Martin Tripp had leaked the data, CEO Elon Musk sent out a now-famous email to the entire company telling employees that there were people trying to sabotage the company –– including from within. Shortly after, Tesla filed a lawsuit against Martin Tripp and fired him immediately.

Through that lawsuit, we now have depositions from Tripp and other witnesses that can help us understand what really happened. First, Tripp explains why he was disgruntled about his job and unhappy with Tesla and his coworkers:

One of the first things Martin Tripp noticed when he started talking to Linette Lopez was that she “definitely has it out for Elon”, but Tripp said he didn’t know why.

What was it that put Tesla and Musk in Lopez’s crosshairs? I can’t speak for Linette, but we do know that the respected financial journalist was close friends with one of Tesla’s largest and most famous short-sellers, Jim Chanos, and had expressed admiration for him in the past. Like other members of TSLAQ, Chanos tweets pseudo-anonymously under the Twitter handle Diogenes (based on the Greek philosopher).

Under normal circumstances, Lopez’s friendship with and admiration of Chanos would likely be mostly unremarkable. After all, she’s a financial journalist and he’s a famous short seller widely praised for predicting the bankruptcy of Enron before it happened. But these were very strange circumstances. For some reason, Tripp seemed to believe that he would be paid $50,000 for providing Tesla confidential information for a news article:

Perhaps unwisely, Tesla CEO Elon Musk pressed Lopez publicly on Twitter trying to get to the bottom of what happened, and even accused her of possibly providing material non-public Tesla internal data to the famed short seller and his firm:

Keep in mind, the depositions from Martin Tripp you see above were not made public until at least 6 months after Elon’s tweets. So while Elon’s tweets were based on Martin Tripp’s actual statements, TSLAQ was able to spin them in a way that made Musk look unhinged, conspiratorial, and hostile to legitimate journalism and criticism. Also, there’s no evidence that Chanos traded on the information before it was published. I suppose it’s possible, but I expect Chanos knows the law and already had a large short position open to profit from the publication of the story anyway.

In response to Elon’s tweets, Lopez tweeted the following which has been pinned to the top of her Twitter profile ever since:

Of course, much like her stories this tweet was completely inaccurate. Someone had shared the Facebook screenshot in a reply to Elon on Twitter –– he didn’t go and find it himself.

But while the internet popped some popcorn to watch the drama between Lopez, Musk, and Tesla short-sellers play out, Martin Tripp watched in horror. Imagine being a factory worker in Nevada and getting sued by your employer –– a multi-billion dollar company. Any lawsuit is stressful, one where your opponent is much wealthier than you are even more so. That’s what Tripp was dealing with when he emailed his former boss a threat:

The next day, Tesla’s call center received an anonymous phone call from a friend of Martin Tripp’s. Tripp’s friend said that Martin was “extremely volatile” at the time due to his firing, and that the release of his name in the media had made him “extremely upset”:

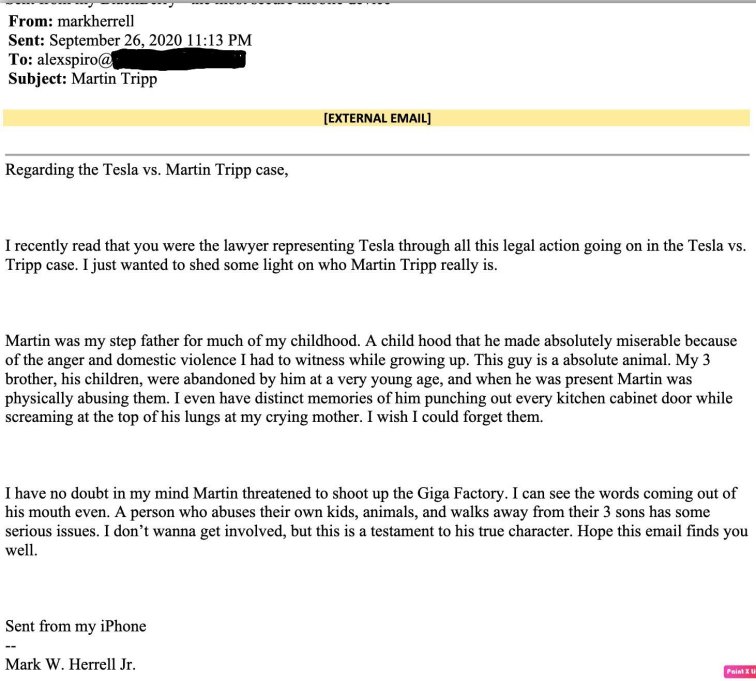

In addition to the call center tip and Tripp’s work history and file, Tripp’s own step-son sent the following email to Tesla’s lawyers about his stepfather:

Later, Martin Tripp sent another email to Elon Musk with another violent threat: “Here is a threat for you: If I ever see you, there is not a bodyguard in the world that will keep me from teaching you a lesson on fucking with the wrong people. I’m done with your dumbass“.

Despite the reality of the situation –– a volatile employee had leaked confidential information to the media, likely in coordination with short sellers –– TSLAQ worked hard to spin the events to support their narrative. TSLAQ was able to take a story about stunning overreach by Tesla short sellers, and spin it as just “another meltdown” by Elon Musk over “all the fraudulent promises” he’d supposedly made (all of which, by the way, have now been released in some form). TSLAQ even claimed that the tip to the call center had come from Elon Musk himself and had been completely fabricated just to harass Tripp for “speaking out” as a “whistleblower” exposing supposed “fraud” at Tesla.

Guess which side of the story the media decided to tell? Tesla’s story about an employee who was told they’d be paid $50,000 in exchange for confidential internal production data? Or the short-seller’s story about a hero whistleblower? Yup, you guessed it. Press coverage universally presented the short-sellers’ narrative: that Martin Tripp was a hero whistleblower, who big bad Elon Musk had tried to “destroy” after a having “a Twitter meltdown” and that the company had “spied and spread misinformation”. The words were printed in Bloomberg, but they sounded like they were coming straight out of TSLAQ’s mouth. Without a doubt, TSLAQ commentary informed the presentation of this story.

So what happened when Elon Musk tried to “destroy” a Tesla “whistleblower”? First, Tripp left the country and moved to Hungary. Ultimately, Tesla and Tripp reached a settlement where Tripp agreed to pay Tesla $400,000, plus another $25,000 for leaking certain court documents. Tripp admitted to violating trade secret laws, and also said that Tesla short-sellers had been footing his legal bills.

TSLAQ tried to spin the stealing of confidential data for payment by short-sellers as “whistleblowing”, but all of the actual allegations Tripp made turned out to be false. For example, Tripp claimed Tesla was shipping battery packs that were unsafe because Tesla had accidentally punctured holes in them during manufacturing. A rumor like that can really scare customers away from buying your product, but no evidence of punctured battery packs has ever been found in any customer car.

Everyone who saw the situation clearly was shocked. TSLAQ had evolved far beyond just spreading nasty false rumors about of Tesla’s impending bankrutpcy. Instead of betting that Tesla would have problems, now they were creating problems themselves. Even so, with the media on their side TSLAQ had come out ahead in the ordeal, gaining a collection of amazing new misleading rumors while Tesla and Musk looked vindictive, unhinged, and against fair journalism. If the media had called TSLAQ out, maybe it would have been the last time they attempted such blatant sabotage of the company they were shorting. But with the media standing steadfastly beside them, Martin Tripp was just the beginning.

July 2018: Vernon Unsworth

TSLAQ’s next successful smear job started when someone on Twitter asked Elon Musk for help. Twelve boys in Thailand were trapped in a cave that was quickly flooding, and someone reached out to Elon to make sure no stone was left unturned in saving them. Elon initially deferred but promised to help in any way he could depending on what was needed.

After consulting with the rescue team in Thailand, Elon had SpaceX engineers build a miniature submarine designed to move kids safely out of the cave in a worst-case scenario where enough water couldn’t be pumped out fast enough to complete the rescue. When it was time to take the contraption to Thailand, Elon went to deliver it personally. The good news is that all twelve boys were rescued from the cave successfully, which meant there was no need to use the submarine. Elon left the vehicle to the Thai government just in case they ever needed to use it in the future.

But TSLAQ couldn’t stand the idea of SpaceX engineers or Elon Musk being seen as helpful, generous, or caring, so they set out to twist the events into a character assassination campaign. How do you make someone devoting time and resources to rescuing children look bad? Like this:

“Oh god, look at Elon trying to get in the news again. The hero rescue team had it all under control, but he couldn’t let them get the credit. He always has to insert himself into any situation even when he isn’t wanted because all he cares about is good press. That stupid submarine would never have worked anyway. It was nothing more than a publicity stunt because that’s all Elon Musk does: stupid publicity stunts to steal investors’ money! What a jackass that Elon is, with his stupid submarine!”

Of course, that’s not at all a fair characterization of what happened. This was something a team of brilliant rocket engineers worked on, just in case it was able to help. Personally, I think it’s incredibly insulting to the SpaceX team that worked on the submarine to try and say it was just about Elon Musk trying to generate publicity. SpaceX and Tesla generate a lot of publicity by doing amazing work and building groundbreaking products. Unlike TSLAQ, they don’t need to pull any stunts to get in the news.

TSLAQ was mostly ignored at first. But then, CNN interviewed Vernon Unsworth. Unsworth was a 63-year-old British cave diver living in Thailand who knew the caves the boys were trapped in well. He was scheduled to make a solo venture into the caves on June 24th when he heard about the missing boys. Given what he knew about the caves, Unsworth advised the Thai government to request assistance from the British Cave Rescue Council. They did, and BCRC divers Richard Stanton and John Volanthen arrived in Thailand to handle the rescue operation, along with many other people from many different organizations including Thai Navy Seals, the U.S. Air Force, and Australian federal police.

At the end of the interview, CNN asked Unsworth what he thought about Elon Musk and his miniature submarine. Unworth said Musk could “stick his submarine where it hurts”, implying with a creepy smile that he’d like to see the submarine inserted into Elon Musk’s asshole:

TSLAQ was ecstatic. “Look!” they screamed from their Twitter pages, “it was a PR stunt!”. Any time Elon would tweet about anything, they would swarm his replies with the Unsworth CNN clip, which was conveniently short enough to fit as a video attachment to a tweet. It was the shining example of TSLAQ’s psychological warfare campaign to unsettle Tesla’s CEO and try and make him appear unstable.

It’s not hard to understand Unsworth’s perspective. He was the one who had actually advised the Thai government to contact the British Cave Rescue Council. This was his moment to be in the spotlight, on international news for probably the first time in his life. And in his brief moment on the world stage, the journalist wants to ask about Elon Musk –– the billionaire whose “mini-submarine” wasn’t even used? From his perspective, Elon’s appearance did seem like a PR stunt entirely unrelated to the diving operation that had actually rescued the 12 boys.

Of course, he didn’t know that British Cave Rescue Council diver Richard Stanton had been emailing Elon Musk, urging him to continue work on the submarine just in case the worst happened. The communications below certainly don’t seem to support the theory that Elon just wanted to insert himself into the situation unnecessarily for good publicity. I think the SpaceX team really wanted to help, and it’s absurd to fault them for trying to help just because the boys were rescued without their submarine. At the same time, I can understand why Unsworth might roll his eyes at the media’s focus on their efforts compared to the work of the rescue divers.

TSLAQ persisted, sending Musk the video of Unsworth over and over again with their own provocative comments until he finally snapped, unable to resist firing back:

On July 15, the New York Times wrote a piece on Unsworth’s comments, and Elon Musk lost his cool. He fired back at Unsworth, challenging his version of events and calling him a name that has come to define the whole saga: “pedo guy“.

TSLAQ had scored. If Elon didn’t look bad before, he definitely did now. The whole dispute just seemed petty, and reinforced TSLAQ’s attempts to cast him as overly obsessed with gaining praise rather than assisting the rescue.

Then there was “pedo guy”. Calling someone involved in a rescue names is rarely a good look, but Elon’s choice of insult drew particular interest and curiosity. “Pedo” is an internet slang abbreviation of pedophile. Surely, Elon wasn’t claiming this man was a pedophile? I assumed he was just firing back by referring to Unsworth’s creepy smile in the CNN clip, but even as a joke it’s never cool to lobby unfounded allegations –– especially when you’re the CEO of a public company with an audience of millions. I’m sure even Elon would agree on that, at least in retrospect.

After a nearly universal negative reaction from the public, Elon apologized for tweeting out in anger and accepted responsibility for the PR disaster he’d caused. But the damage to his credibility was done. TSLAQ had scored once more in their game of psychological warfare.

But TSLAQ wasn’t done just yet –– they were having way too much fun demonizing Musk, especially as Tesla stock sustained an 11% decline over the month of July. They feigned outrage at the internet name calling (despite their own tweets), and urged Unsworth to sue Elon Musk in the name of justice (and profits). They even found a lawyer willing to represent Vernon Unsworth on a contingency basis, meaning Unsworth would pay nothing unless he won.

As the case was filed and moved forward, TSLAQ praised the lord, hailing the libel suit as the trial of the century, concerning history’s biggest crime. Finally, they claimed, everyone would see that the emperor had no clothes. Finally, they hoped, everyone would hate Elon Musk. It’s not the kind of thing you want to be in the news for. As the trial approached, TSLAQ praised Unsworth’s lawyer L. Lin Wood, hailing him as the second coming of Christ:

TSLAQ lavished praise upon Unsworth’s attorney… until he lost the case. Then, all of a sudden, they weren’t thinking of him at Thanksgiving anymore. Once Wood lost the case, TSLAQ turned on him at the drop of a hat. They insulted, harassed, and smeared the man just as they had done with so many others:

August 2018: Funding Secured

Morale was low among people rooting for electric vehicles. On top of very real difficulties with Tesla’s business and the struggles of ramping up Model 3 production, TSLAQ was landing blow after blow after blow. The situation was concerning: If Model 3 failed, the entire concept of electric vehicles would be written off for another generation. If it succeeded the entire global auto industry would rush to follow, with regulators putting wind in their sails worldwide.

The stakes for Tesla –– and for sustainable transport –– couldn’t have been higher. But TSLAQ short sellers were winning the messaging battle and becoming a huge problem. Successfully launching a new car model at a company that’s never mass-produced a car before is already nearly impossible. Trying to do that with a car that’s electric, and completely new and unfamiliar to most Americans is stupidity squared from a business perspective. But trying to do all that while a group of highly motivated, extremely vocal, and well-connected short-sellers are waging a brutal social media disinformation campaign to try and destroy your business while assassinating your character? Boy, chances of success start to look pretty slim.

Elon knew he’d have to get creative –– he hadn’t been winning the way he was playing. SpaceX was going through many similar issues to what Tesla was facing, but short-sellers didn’t target the business nearly as much. It wouldn’t have been very easy to make money doing so: SpaceX is a private company. After meeting with potential investors in August 2018, Elon started to consider a wild idea that could protect Tesla shareholders from TSLAQ’s short and distort campaign: Take Tesla private again, just like SpaceX.

It was a questionable idea for several reasons. Although companies like Dell had successfully gone private, this would be a huge complicated ordeal that would distract from running the business. On top of that, private companies are only allowed to have a certain number of shareholders under U.S. securities law. Would that mean that most Tesla shareholders would be forced to sell? Most did not want to. Finally, who would fund what would have to be the largest go-private transaction ever?

To make matters worse, the deal as Elon described it –– where shareholders could choose to sell at $420 or keep their illiquid private shares –– did not seem to be possible under U.S. securities law. A company that is owned by thousands of people is a public company and must follow all laws designed to protect investors in public equities. Simply taking the shares off the stock exchange doesn’t change anything –– almost all shareholders would need to sell to complete the go-private transaction. A generous interpretation of these events would be that Elon Musk simply didn’t understand that what he was describing was complicated and likely impossible. A more cynical observer might say that he knew the idea wouldn’t work, but tweeted during market hours in an attempt to deliberately manipulate the stock price and “burn the shorts”, causing large unexpected losses for Tesla short-sellers.

Indeed, the shorts were burned. Within seconds of the tweet being posted, Tesla stock soared towards an all-time-high of $380, reversing a downward trend:

Elon only said he was “considering” taking the company private, so the $380 share price reflected the market’s uncertainty over whether the deal would come to pass. (If investors were certain they would be able to sell each share for $420, you would expect the share price to quickly move close to that number). But TSLAQ was furious. Their blood boiled with rage as watched trading losses pile up on their Tesla short bets. One famous short seller, Andrew Left of Citron Research, claimed in a report that he lost $2 million instantly after the “funding secured” tweet. He was angry enough to sue Tesla over the losses, but ultimately gave up on shorting Tesla and changed his position on the company two months later.

TSLAQ screamed at the top of their lungs. They were in shock. They couldn’t believe what was happening, and vowed to seek revenge. Their hatred for Musk and Tesla had reached emotional new heights. They demanded to know immediately who was providing funding for the potential transaction, casting aspersions on Musk and implying that he had completely lied about the transaction just because he wanted to make them lose money. Tesla responded in a blog post clarifying that the funding could be obtained from Saudi Arabia’s PIF, possibly through Softbank’s Vision Fund. But this posed yet another problem –– a large foreign investment of this size would require a CFIUS national security review, with no guarantee of approval. With little more than a handshake agreement, the funding did not appear to be as “secured” as the tweet made it seem. Maybe Musk had gotten a little too excited to “burn the shorts”, and TSLAQ was not going to let it slide.

When Tesla announced soon after that it would stay a public company, short-sellers were ready to riot. They shouted until they turned blue, spitting in the face of anyone who had the misfortune of coming into contact with them. They complained to anyone who would listen: Social media users, journalists, and even their friends at the Securities and Exchange Commission, who often depend on research from short-sellers to help them enforce securities laws.

TSLAQ’s complaints were successful. Famously, the SEC took action against both Elon Musk and Tesla in an action that threatened to remove Musk as CEO of Tesla via a D&O ban. The next day, Elon settled with the SEC by agreeing to pay $20 million, with Tesla also paying a matching fine. Musk then bought $20 million worth of Tesla shares immediately after the fines were paid. Despite the fines, Elon Musk joked that it was “worth it” to see short-sellers lose money:

TSLAQ had scored once again, big time. It was the pièce de résistance on the golden summer of short and distort. Vengeance was sweet, and TSLAQ could not have been more thrilled. They screamed “FRAUD!!!” louder than ever, and for the first time, they had something real they could point to: a settlement with the SEC. Like the Unsworth case, they spun the funding secured incident as the greatest crime in history. Meanwhile, Musk openly expressed his frustration at the SEC by publicly calling them the “Shortseller Enrichment Commission”, furious that they had ignored his grievances surrounding a brutal short and distort campaign and handed a victory to his enemies instead.

Meanwhile, Tesla shareholders gulped. Suddenly, TSLAQ’s ridiculous conspiracy theories didn’t seem so funny anymore. The reality of the situation was suddenly undeniable to everyone involved. Tesla short sellers had become a serious danger to the future of the company, and they were winning. They were landing blows that nobody thought possible –– Tesla bulls couldn’t believe that the possibility of Elon Musk being forced out of company had seriously been in the news, even if it was just for a day.

Tesla bears were waking up too. Working together, they were far more powerful than any single individual TSLAQ member could have imagined on their own. They were starting to get smug, and every financial journalist covering Tesla wanted to know what the Tesla short-sellers had to say. Everyone loves a controversy, and Tesla would generate clicks, views, and retweets like no other subject. Finally, TSLAQ had the ears of the world. They were angry, emotional, and thirsty for blood –– ready to use their newfound influence to destroy the company that made the car I loved.

The news I read about Tesla seemed to be from an alternate reality. The entire conversation around Tesla had been consumed by TSLAQ, and almost no one except Tesla customers seemed to remember the products. It took me a while to figure out what was really happening, but once I started to grasp it I realized there was no way customer voices could possibly compete with this swarm of anonymous trolls with only their personal Twitter accounts and real names. Even pointing out just a small fraction of TSLAQ’s lies and misleading narratives from my @OmarQazi account, I felt bad spamming my followers with so much Tesla discussion.

The TSLAQ campaign was still completely ridiculous, but few people saw it that way. Although the TSLAQ thesis often centered on implausible conspiracy theories, it was the center of the Tesla story. Having followed TSLAQ for months I wanted to point out the absurdity of the situation as I saw it, but how? There was no way I could ever adequately debunk the trolls from my personal Twitter account, I realized one night in November. TSLAQ’s manipulative disinformation tactics couldn’t be challenged with polite questioning, assuming honest intentions. No –– to debunk this swarm of trolls, I’d have to become one myself.

Read Chapter 5

Aaron Greenspan has filed an illegal SLAPP-suit against Elon Musk and Omar Qazi for bringing attention to allegations of tax fraud, securities fraud, cyberstalking, and criminal harassment by the Think Computer Foundation (doing business as PlainSite). If you can please donate to the Legal GoFundMe or via PayPal to make sure Aaron Jacob Greenspan is finally held accountable for his harassment of so many Tesla customers.

History that must be preserved. Maybe a book someday? Massive respect to you, Omar.

THANK YOU.

Wow great recap and story. This all would make a great book to be published =]

What about a Netflix docu?

Thanks for putting it all together, even that I was seeing/experience it all, one forgets! Good to have all history in one place!

This is OUTSTANDING work. I never knew TSLAQ went this deep.

hahah this is nothing, this story is about to get crazy around chapter 6

Great job documenting this. It brings back memories. I was one of those on the TSLAQ blocklist. I agree with others, this should be a book. There are so many people that still have the wrong idea about Elon Musk, but those who have been watching this play out for years know how much of an amazing person he really is. When I traveled to San Francisco I thought I was in the land of really smart people who would see things for what they really were so I started conversations with people about Elon Musk and Tesla only to find out they had old wrong information about Elon and his companies.

I wonder if the block list didn’t start out as an echo chamber but as a way to focus their efforts on the customers and supporters of Tesla. This way when they saw a new supporter they would know they hadn’t yet sent them all the reasons why they shouldn’t have bought that Tesla.

When you write that book, remember to mention the Thai General in charge of the cave op. told journalists (including tweeting directly at a Guardian journo whose name I sadly don’t recall) he personally asked SpaceX for help because he had a friend who worked there. Guardian and all media who also knew, ignored it and continued pushing the Musk god complex/forcing himself into the story line.

Smear stories may have TSLAQ help but MSM show their true colours by vilifying Musk as often as possible (and Tesla) and are directly responsible for the public’s (ongoing) poor perception of both.

ah, forgot about that thanks for the reminder. maybe i’ll do some research and add that part in

While 2020 was rife with Muskian drama with Tesla and SpaceX giddy valuations, edgier, sexier memes, the anti-vac/FREEDOM stuff, EDM, a Grimes baby and a spectacular Starship RUD, reading this reminds me of how 2018 was truly out of this world. Elon really does his best to keep the simulation interesting and his efficiency is mind-blowing. I can’t wait to see what crazy hijinx is coming up: beating NASA back to the moon for the lulz, a sub $25,000 Tesla, read/write Neuralink in humans, upgraded space lasered Starlink and not least, catgirls…possibly on Mars.

I would have also enjoyed seeing the alternate reality in which he manages to acquire Russian ICBMs for Mars Oasis and grows weed on Mars. I like to imagine it had a non-zero probability of happening.

Scriptwriters will draw from this when the Grand Epic Story of Tesla is written for the silver screen.

Nice work Omar.

I have been a Tesla shareholder since 2013 and I remember all of this clearly. It did feel like they had total control around the time of the SEC fine. I was so frustrated with how the mainstream media just relentlessly printed negative news. All of it was clearly based on the nonsense these clowns spouted. There are at least a dozen journalists that were and still are influenced by outside forces.

Once the Model 3 ramped up and the Gigafactory in China came online they became a lot less relevant. These days, we can all look back and laugh at these morons. In some ways I should be glad they stopped so low and persisted for so long. I added to my position with each pay cheque. My view was that Tesla is a juggernaut that would become the world’s biggest company. The price of TSLA was a once in a lifetime bargain opportunity. I now own 5,570 shares in TSLA and as a result I am a Teslanaire. Without these clowns I wouldn’t have been able to accumulate as much. Thanks TSLAQ.

Also started to buy TSLA in 2013, just before Q2 report, at $50-level. Now have more than enough to comfortably retire.

The other day I knew that name was familiar but couldn’t quite remember why until reading this chapter. Like a broken clock, tslaq can be right once in a while: L.Lin Wood does not seem to be a shining star such as the current constellation of Jupiter and Saturn. A complaint over the election in Georgia was signed “under plenty of perjury” — no kidding! Downloaded a pic och the doc from Twitter, but I can’t figure out how to upload it here. Anyway, I swear that’s what it said! 😉

Thank you very much for standing up to the bad bullies, Omar! Keep it up and bring them down! (I have contributed to the legal fund.)

Thank you so much 🙂

how far along is ch 5?

should be posted today