If you can, please donate to the legal fund via GoFundMe or PayPal.

Previous Chapter: Trolling the Trolls | Next Chapter: Who is Aaron Greenspan?

Greenspan’s Birthday Gift

I was 25 years old the day Aaron Jacob Greenspan doxxed me. I remember, because he did it on my birthday. While everyone was sending me birthday wishes on Facebook, the supposed creator of Facebook wanted to give me a different kind of gift –– the kind you’re forced to carry for the rest of your life.

I thought it was going to be a good birthday. My friends had planned a surprise for me after work, so I was in a good mood. While I was waiting for some code to compile I opened Twitter to do what I always did when I had a free moment: browse the timeline to catch up on news, debunking any false or misleading info about Tesla I found along the way. Whenever I commented on a news story that was unusually deceptive, I would also try and do some research on where it came from, who was behind it, and what their motives were.

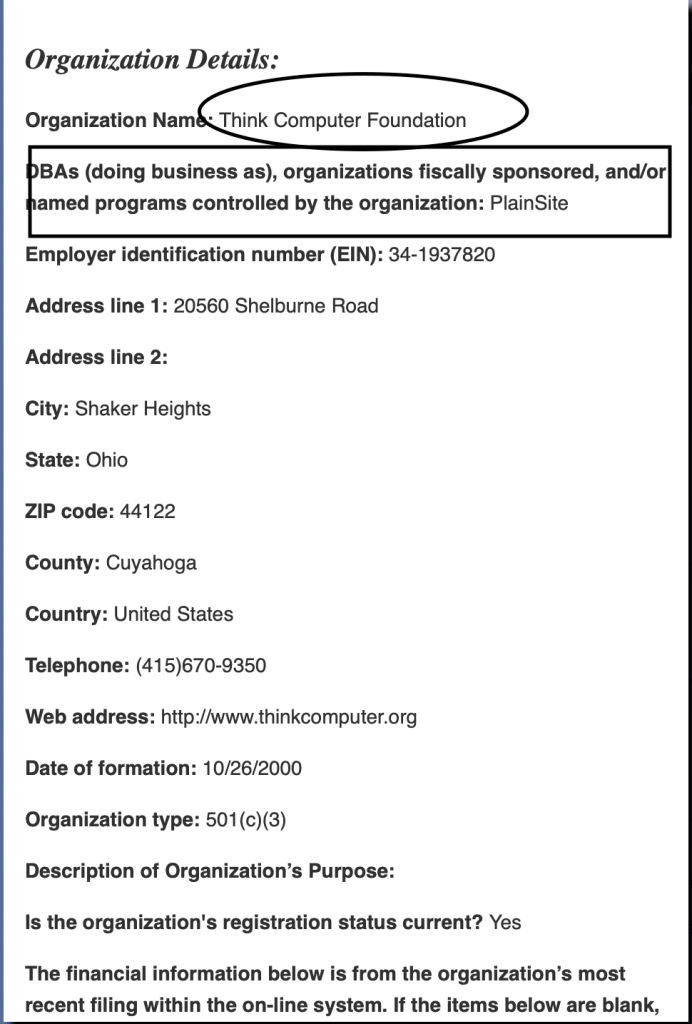

On that fateful day, the Twitter timeline algorithms happened to send me a tweet from an account called “PlainSite” claiming that Tesla’s Model 3 had a problem with the screen freezing. I posted a screenshot of the tweet, along with my opinion that the Model 3 had what was hands down the most amazing, most responsive touch screen I’d ever seen in a car. It was so much better than anything else –– like an iPhone touchscreen compared to those old plastic ones you had to push in. Whoever was tweeting as “PlainSite” had clearly never used a Model 3 touchscreen before.

PlainSite in the News

I had seen PlainSite mentioned in the news several times, and they were always tweeting negative info about Tesla –– it wasn’t the first time I’d seen anti-Tesla tweets from that account. I wondered: What was this organization I had been seeing in the news, and what did they have against Tesla?

Back then I was honestly genuinely confused by where the TSLAQ movement was coming from: Were these really people? Was this something set up by Russia or Saudi Arabia to hold back clean energy? Was it the oil industry, the legacy auto industry? Wall Street hedge funds? Even though @tesla_truth was supposed to be funny, I genuinely wanted to know. As I explored and researched the topic, I would share what I found on Twitter.

Most TSLAQ accounts kept their identity secret, but not PlainSite. When I googled the non-profit charity, the answer was right there: “PlainSite is run by Aaron Greenspan”. Well, who the hell is Aaron Greenspan? Is that a real person? Kids, heed my advice: Don’t ask questions you don’t want to know the answer to.

The Inventor of Facebook

The Google results for Aaron Greenspan’s name were filled with stories where Aaron claimed he had invented Facebook. I burst out laughing –– it was too funny to be true. I’d had some great times on Facebook in college and high school, where Facebook was an essential communication tool and a core part of academic life. The Social Network was and still is one of my favorite movies, even more so now that I know how much Aaron hates it (because he’s not in it). To state the obvious, Aaron Greenspan did not invent Facebook. Not at all. Not even a little bit. Based on that, my first impression of Aaron was that he seemed at least a little bit delusional.

That’s what was so funny to me: Here was this guy saying Tesla was a total fraud that was about to go bankrupt, which didn’t match my experience or predictions for the future at all. He was trying his best to convince everyone, and seemed to be extremely well connected with mainstream journalists. But wait –– just a few years ago he was telling everyone he invented Facebook. How seriously are you going to take the guy who honestly believes, from the bottom of his heart (assuming he has one), that he is the inventor of Facebook and Mark Zuckerburg just stole the idea from him?

It’s like if you asked someone for directions to the mall, and they told you they just flew there on the back of a gorilla. They might follow up by pointing you in the right direction, but you probably don’t want to take anything they say too seriously. At the very least, you’ll want to double-check those directions. Naturally, I had to tweet about how Aaron Greenspan, the guy posting anti-Tesla tweets as “PlainSite”, seriously believed that he invented Facebook.

Direct Message Warnings

My @tesla_truth account had just around 300 followers at the time, and many of them found Greenspan’s claim of inventing Facebook as funny as I did. But in addition to liking and commenting on the tweet, my direct message inbox (which was open to anyone) instantly lit up with half a dozen messages from different people offering more information about Greenspan and his charity. It seemed there were a lot of people on the internet who didn’t like Aaron, and they warned me to be careful tweeting about him. Many said that they were afraid of him. Some of the accounts messaging me about Greenspan also mentioned he was in court dealing with a restraining order that week.

I was instantly intrigued. This Greenspan guy seemed like quite a character, and a nasty one at that. Were these the kinds of people behind TSLAQ? I went to check out PlainSite online, which purported to be a charitable website run by a non-profit that allowed anyone to search public data. To try and figure out how the website worked, I entered my own name and saw that there were no results. I then entered the name of my startup, Smick, assuming there would at least be basic public registration info –– but there was nothing. I concluded that PlainSite wasn’t actually searching public databases at all, and instead only contained information that Aaron Greenspan had manually collected, selected, or published himself.

Most of the Twitter messages I received about Aaron Greenspan seemed to be true. I never looked it up until I started researching this story, but it turned out Greenspan was in fact in court dealing with a restraining order the day after my birthday:

I went back to my Twitter thread about Greenspan claiming he invented Facebook, and added a new tweet mentioning the court hearing over a restraining order taking place that week. The next time I checked my Twitter Direct Message Inbox, there were even more messages about Aaron Greenspan –– including one from @AaronGreenspan himself.

To be honest, I was a little star-struck. I was just a little random Twitter account with a few hundred followers. I talked about things I saw in the news every day, but very few people cared. I’d never had someone in the news I was covering actually message me before. I was surprised and amused: Cold that really be Aaron Greenspan himself?

But Greenspan was not amused at all. He was enraged, and began threatening me from the very first message he sent:

Aaron Greenspan’s Threat

Aaron Greenspan’s message said “Please delete the following:”, followed by a URL shortened link. At this point, I didn’t think anything unusual was going on. It was my birthday, and I had just tweeted about something I’d seen in the news like any other day. My goal was not to harm Aaron, defame him, or spread “false information”. I was just tweeting my own thoughts and opinions, with the best information I had.

Anyone was welcome to message me politely if they had a problem with a tweet or believed it was inaccurate. They could even reply publicly if they wanted to. Most times if someone was upset about something or corrected one of my tweets, I would just delete it. They’re just tweets after all, and the objective was never to be an asshole or harm anyone. Given all that, when Aaron Greenspan messaged me I wanted to hear out his concerns and remove or correct any false tweets if necessary. That’s why I clicked on the link to see what exactly he wanted me to delete.

Based on what I already knew about Aaron Greenspan, I should have known better than to try and have a conversation with him man to man. It turned out the purpose of the link wasn’t to show me what he wanted deleted at all. Instead, he had set a trap. The link pointed to an image file on his web server, allowing him to monitor the server logs for the IP address of my San Francisco apartment. Once he had the IP address, he could cross-check it against PlainSite’s search history from the same IP, and as luck would have it my search history included my own name. In retrospect, I should have been more careful, but I thought that I was playing around with a charity’s website. It never occurred to me that the site owner would threaten me and attempt retaliation simply for tweeting about the news.

Aaron Greenspan’s threat was simple: Delete the tweets about me, or else. Or else what? He made it crystal clear: If I didn’t immediately delete the tweets about him he promised to doxx me, which is internet slang for when you post someone’s identity and personal information online against their will and without their consent in an attempt to incite harassment towards them. The idea is to make them fear for their safety so they do what you want.

I was shocked that Greenspan cared so much about a random Twitter account with a few hundred followers, and wondered what would be the right thing to do. If Aaron had messaged me saying, “Hey can you please delete that tweet. It’s inaccurate because of x, y, and z”, then I would have listened to him. Using a misleading message to obtain my IP address by force and threatening retaliation unless I stayed silent about him seemed to suggest that most of what I’d heard about Aaron Greenspan was true –– this was a really nasty guy. Deleting the tweets would have been the easy and safe thing to do, but how many other people had Greenspan and his “charity” silenced? How many more would he target if no one was brave enough to speak up?

This was TSLAQ: People like Aaron Greenspan. These were the nasty people spreading false negative information about Tesla I had started @tesla_truth to learn about. With that in mind, I decided to take a risk and keep the tweets up for the public good. It seemed like the right thing to do. What was the worst Greenspan could do to me over a tweet? On top of that, although I didn’t know it at the time Greenspan’s threat was a blatant violation of the Twitter rules.

Twitter’s Private Information Policy clearly states:

You may not publish or post other people’s private information without their express authorization and permission. We also prohibit threatening to expose private information or incentivizing others to do so.

Sharing someone’s private information online without their permission, sometimes called doxxing, is a breach of their privacy and of the Twitter Rules. Sharing private information can pose serious safety and security risks for those affected and can lead to physical, emotional, and financial hardship.

Twitter Rules

In addition, Twitter’s policy on the distribution of hacked materials states:

What is in violation of this policy?

We define a hack as an intrusion or access of a computer, network, or electronic device that was unauthorized or exceeded authorized access. Behaviors associated with the production of materials which would count as a hack under this policy include:

Unauthorized access or interception, or access that exceeds authorization (for example, from an insider), to a computer, network or electronic device, including breaches or intrusions

Disclosing materials where there is evidence that they were obtained through malware or social engineering

Twitter Rules

Greenspan’s fake URL shortened link to his web server, sent under the guise of an honest request, was an act of social engineering designed specifically with the objective of unauthorized access and interception of my personal information. Under Twitter’s definition of a hack, all of the materials obtained via this trick screenshot link constitute hacked materials in violation of Twitter’s rules.

More broadly, Aaron Greenspan’s threats also violated Twitter’s rules against abusive behavior and harassment.

Twitter Rules: You may not engage in the targeted harassment of someone, or incite other people to do so. We consider abusive behavior an attempt to harass, intimidate, or silence someone else’s voice.

Rationale

On Twitter, you should feel safe expressing your unique point of view. We believe in freedom of expression and open dialogue, but that means little as an underlying philosophy if voices are silenced because people are afraid to speak up.

In order to facilitate healthy dialogue on the platform, and empower individuals to express diverse opinions and beliefs, we prohibit behavior that harasses or intimidates, or is otherwise intended to shame or degrade others. In addition to posing risks to people’s safety, abusive behavior may also lead to physical and emotional hardship for those affected.

Twitter Rules

There’s no other way to spin it: Greenspan’s threats to doxx me if I didn’t delete the tweets about him were an attempt to harass me, intimidate me, and silence my voice. Many people have suffered physical and emotional hardship, myself included, because PlainSite is somehow still allowed on Twitter.

Naturally, this was far from the first time Aaron Greenspan and his “charity” PlainSite had violated the Twitter rules. Previously, the PlainSite account had been permanently suspended multiple times from Twitter for sharing people’s private information without their consent, in violation of Twitter’s policies:

In addition, his personal @AaronGreenspan account had been suspended as well:

It breaks my heart to see that Greenspan was suspended from Twitter in October 2018, but somehow managed to convince administrators to restore his account. October was one month before I created @tesla_truth, and three months before I first encountered Aaron Greenspan on my 25th birthday. If they had just kept his account suspended, all the pain, suffering, harassment, and stalking I’ve endured over the last two years never would have happened. With Greenspan’s “charity” Twitter account restored, he was free to violate the policy again and strike his next victim. And strike again he did, violating the exact same private information policy he was suspended for again on my birthday.

Birthday Doxxing

When I refused to bow to Aaron Greenspan’s threats and delete the tweets about him, he made good on his word and doxxed me within an hour.

Greenspan insulted me by calling me a failure, and then began stalking me. He looked through all my posts to make one thing clear: Every move I made would be followed so that he could hurt me if he needed to. He revealed my real name without my consent and used photos I had tweeted to track my movements. He then shared the name and location of my family’s business which he found by looking at my LinkedIn profile. This was concerning because my family and a lot of people I cared about worked in that office, and I didn’t want anyone to hurt them. Since the company only had one office, anyone who saw his post could use it to easily find me in real life.

Sure enough, I immediately started receiving strange threatening text messages, phone calls, and letters after the doxxing. People would say things like “I’m at Del Taco”, referencing a restaurant next to our office building to imply that they were close by and watching me, ready to act at any time should I cross TSLAQ.

Despite Greenspan’s threats and doxxing souring my birthday, I tried to shrug it off. “Don’t let this creep get to you, that’s what he wants”, my friends told me. I tried to forget the strange text messages and calls, hoping it was just someone messing with me for reasons unrelated to Greenspan doxxing me. “So what if Greenspan shared the name behind my @tesla_truth account?”, I thought at first. Unlike TSLAQ, I wasn’t tweeting to manipulate the price of stocks and felt that I had nothing to hide.

I was naive. I could never have imagined the lengths Aaron Greenspan would go to in order to try and make my life hell. This is a guy with no job, no life, and nothing to do except torment his perceived enemies –– including people and journalists who did nothing more than say Mark Zuckerberg invented Facebook. People in my Twitter DMs warned me, “be careful, this guy will ruin your life” but I didn’t take them seriously enough. What was the worst he could do, and how much did he really care about some random guy’s tweets? Looking back, I wish I’d taken all the warnings about Aaron Greenspan in my direct messages to heart. When the Twitter rules talk about “physical, emotional, and financial hardship”, that’s not abstract for me anymore. I’ve lived those words, and understand them more deeply than anyone should have to.

Immediately after doxxing me on Twitter, Aaron Greenspan placed a phone call to the office of our family’s business. He demanded that the company fire me immediately, or face retaliation. After he got off the phone with the company, he attempted to contact my Dad. I found out the next day when my Dad asked “Who is Aaron Greenspan?”. I couldn’t believe he would do so much over a few tweets. This guy was really every bit as crazy as I’d heard.

Doxxing Aftermath

After Greenspan called my office and my Dad, I decided to return his call myself. I found his phone number on the PlainSite website and gave it a call. But as the phone rang, I thought better of it. The guy was clearly crazy, and any attempts to talk to him would likely only lead to more tweets and harassment targeted in my direction. So when he picked up the phone, I pretended to be a telemarketer working for the phone company until he hung up.

I wasn’t too eager to tweet about Greenspan and face further retaliation, but I still mentioned him sometimes when he said something crazy or I saw him in the news. Aaron was not ready to let it slide: Every time I tweeted about him, I faced false accusations and threats to remind me to stay quiet or else.

For example in retaliation for some tweet I can’t remember, Greenspan accused me of illegally selling shares in my company to strangers online. U.S. securities law only allows selling shares in private companies when certain conditions are met, so he essentially falsely accused me of violating securities laws. Of course, Smick had never sold any shares to the public but that didn’t matter. By falsely claiming “you can buy shares online” Greenspan sent a clear message: Keep quiet about me and my business, or I’ll target your business. He also threw in another lawsuit threat for good measure, as a way to try and scare people away from any involvement with my company.

In another example, he falsely accused me of running a red light. The copyrighted video he stole and re-uploaded to his “charity” Twitter and YouTube accounts included the location where the car was driving, as part of Greenspan’s continued efforts to stalk and track my location from my public posts. Besides the fact that an accusation of running a red light is absurdly trivial, I wasn’t even the person driving the car in the video. I had just posted it to demonstrate that Autopilot had recently added the ability to detect red lights and warn the driver to stop if needed. It was just a regular part of my coverage of Autopilot, which often involved posting videos from others on a daily basis.

To prove that I was the driver in the video, Greenspan’s charity Twitter account stole a copyrighted photograph of my car with my license plate exposed and tweeted it below the video. Of course, this photograph offered no proof at all. While it’s true my Model 3 was black, that was the “default” color for the Model 3 at the time –– the only color choice that came at no extra cost. Pretty much everyone my age stretching to afford a Model 3 picked the default color at the time. The real purpose behind sharing a photo of my car was for Aaron to continue to harass me, stalk me, and share my personal information online with people who wanted to harm me. “Great”, I remember thinking, “Is someone going to recognize my car and license plate and vandalize it now?”. I loved that car, so it wasn’t pleasant to think about. Greenspan admitted he wasn’t even sure I was driving the car but still chose to expose more of my personal information anyway, not to mention the address of my friend’s apartment in Los Angeles.

Just like the birthday doxxing, I laughed off Greenspan’s attempts to harass and threaten me as minor annoyances. In a way, it was almost kind of funny to see him obsess about me so much that he had to constantly hurl false accusations of minor crimes like “running a red light”. At least at first, Greenspan’s attempts to threaten me into silence fell flat on their face.

Black Mail

A few weeks after Aaron Greenspan doxxed me on my 25th birthday, I received a black envelope in the mail at our office that was slightly more concerning. Inside there was no letter, and no words at all: Just the photo from when I got caught with weed at Holy Ship. I gulped hard. My parents still didn’t know about what happened, and I wasn’t too eager for them to find out. With a one-word change in the mailing label, that envelope could have been sent to my Mom or my Dad. That piece of mail had no words, but the message was clear: If you continue talking about Aaron Greenspan and his “charity” PlainSite, this will come out. I was being blackmailed, somewhat literally.

I couldn’t believe what was happening. I had never expected my stupid “Steve Jobs” account to illicit such a crazy response. Now I was being stalked and threatened, all because I tweeted about some “charity” that inexplicably hated Tesla. I should have gone to the police then and there, but I just threw the letter away in a public dumpster a few miles away from the office since I was afraid of someone seeing it in the trash. I hoped that if I ignored it, it would all just go away. Unfortunately, it never did.

How could this be happening? What kind of charity stalks, harasses, and threatens critics online –– even if they only have a few followers? If I was going to protect myself, I needed to learn more about Aaron Greenspan’s “charity”, the Think Computer Foundation (doing business as PlainSite) –– and about Aaron Greenspan himself.

Read Chapter 7

Aaron Greenspan has filed an illegal SLAPP-suit against Elon Musk and Omar Qazi for bringing attention to allegations of tax fraud, securities fraud, cyberstalking, and criminal harassment by the Think Computer Foundation (doing business as PlainSite). If you can please donate to the Legal GoFundMe or via PayPal to make sure Aaron Jacob Greenspan is finally held accountable for his harassment of so many Tesla customers.

Greenspam is literally the worst lol

hahahah I know litterally the worst guy ever 😂

Ikr!!! And he’s competing against 7.594 billion people so it’s not like that’s an easy task! He might not have invented facebook but he’s a champion in my book, brother.

🤣🤣🤣

Love the posts, there needs to be a book written about the Tesla shorts though.

Must be named, “the short shorts”

When do we hear more about Jim? 😉

chapter 8 hahahaha